Born with a congenital heart defect, John MacEachern faced a grim prognosis. (Photo: John MacEachern)

John MacEachern, now 73, remembers his ninth birthday clearly: he spent most of it jumping up and down, screaming, "I beat them!"

The memory is so vivid because when he was born, MacEachern was given only eight years to live.

He had been born with a four-part heart defect – Tetralogy of Fallot – that limits the amount of oxygen in the blood and leaves patients with low energy and dizzy spells. Tetralogy of Fallot couldn't be properly repaired until 1954 – 13 years after MacEachern was born, and six years past his prognosis.

MacEachern survived due to the innovation of a doctor at Toronto General Hospital in 1945 and the brave determination of his parents.

A novel repair

MacEachern's parents, unwavering in their quest to help their son despite his grim prognosis, asked every doctor they met if there was a way to save him. One Christmas party, they found the answer they were looking for.

The four elements of Tetralogy of Fallot:

-

Ventricular Septal Defect – A hole in the wall separates the heart's pumping chambers (ventricles). This hole allows high-oxygen blood from the left to mix with low-oxygen blood from the right, changing the levels of oxygen content in the blood.

-

Pulmonary Stenosis – The valve that connects the right pumping chamber (ventricle) to the lungs is narrowed. The heart must work harder to get blood to the lungs. Not enough blood reaches the lungs. The blood is never properly oxygenated.

-

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy – Because the right pumping chamber has to work harder to pump blood to the lungs, the muscle on the right side of the heart thickens.

-

Overriding Aorta – The aorta is not in the right place (it is located near the hole in the heart's chambers) and rises above both pumping chambers (instead of just the left pumping chamber). This allows the heart to pump low-oxygenated blood throughout the whole body.

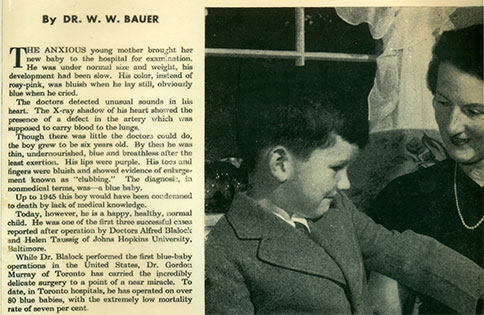

Dr. Gordon Murray, a surgeon at Toronto General at the time, told them a surgery had been done to help Tetralogy of Fallot patients in the United States.

"He told them, 'leave it with me,'" MacEachern recalls. "Then he went down to the John's Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to meet with Dr. Alfred Blalock and Dr. Helen Taussig, who had created this new shunt and shifted survival perspectives of many children born with tetralogy of Fallot."

Later named the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt, the procedure involved the surgical creation of a shunt from the left or right subclavian artery (which supplies blood to the left or right arm, respectively) to the right or left pulmonary artery to re-direct low-oxygen blood to the lungs. This would increase oxygenation in the lungs and the amount of oxygen in the blood.

The procedure had only been performed twice in the world, and only in the United States.

A Canadian first

"He told my parents that it could be done, but there was a great risk," MacEachern says. His parents were resolute. At the age of four, they "gave me up to science," he says, and agreed to the surgery.

There was work to be done.

Nowadays, blood supply during surgery is left up to the hospital and its partners, but at the time MacEachern's parents had to collect all the blood necessary for the surgery. His parents' colleagues, fellow members of the church and teachers at his siblings' schools donated blood to the cause.

The day before his surgery, MacEachern remembers his mother sitting with him and telling him: "Tomorrow you'll go to the hospital, and the doctors will fix you."

In 1945 at Toronto General, MacEachern – then only four years

old – became the first patient in Canada implanted with the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt.

An innovative procedure performed by doctors meant that John MacEachern could survive well past his prognosis. A photo and article of him was featured in Maclean's Magazine two years after the procedure. (Photo: John MacEachern)

'I thought I was fixed'

After a turbulent first four years, MacEachern's life improved drastically after the surgery. There were no more dizzy spells, no more recesses spent inside and no need to be carried around the house. MacEachern felt stronger.

"In my mind, I was fixed," he says.

Then, at age 50, MacEachern was skiing at Mont Tremblant with his family when he passed out. He was immediately rushed to a local hospital where a doctor asked him when he had last seen a cardiologist.

"I said, 'Why? I'm fine! I was fixed!' The doctor was shocked. He said to me, 'Mon dieu!' and told me to see a cardiologist as soon as possible."

That incident at Tremblant led MacEachern to Dr. Bill Williams, a congenital heart surgeon from the Hospital for Sick Children, who performed a more complete repair on MacEachern at Toronto General Hospital.

It turned out that MacEachern wasn't fixed – he only received a palliative shunt to improve oxygenation of the blood in the lungs and to help him survive. Now, the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt is implanted only as a bridge to a full repair. MacEachern didn't get a more complete repair until it was nearly too late.

"The misconception of being 'fixed' is very common," says Dr. Erwin Oechslin, Director of the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program and Bitove Family Professor of Adult Congenital Heart Disease at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre. "Thirty or more years ago, pediatric cardiologists and surgeons didn't have any long-term outcome data and couldn't anticipate long-term complications. This has changed now."

Now, Dr. Oechslin explains, patients born with congenital heart defects are told that they will need lifelong follow-up. Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) patients are at risk of re-interventions for leaky or narrowed valves, heart failure, heart rhythm disorders and sudden death. Constant follow-up gives doctors a chance to intervene early, Dr. Oechslin says.

"Most CHD patients are never fully cured," he explains.

Now 73, MacEachern is retired and writes mystery novels. (Photo: John MacEachern)

Becoming a patient advocate

MacEachern went on to become the president of Canadian Congenital Heart Alliance, advocating for the health and survival of patients like him – born with a condition that was once largely seen as fatal.

"I feel pretty grateful every time another birthday comes around," he says.

Now retired, MacEachern writes mystery novels and watches from afar as the CHD community continues to grow.

"Sixty years ago, there was a natural selection and only 20 per cent of children born with a congenital heart defect survived until adulthood," says Dr. Oechslin. "Today, more than 90 per cent of patients with even a complex congenital heart defect survive until adulthood due to great advances in medicine, imaging, congenital surgery, intensive care and nursing."

As outcomes improve for CHD patients, both Dr. Oechslin and MacEachern hope to see more resources made available to these patients.

"This rapid growth of a new generation of congenital heart disease patients – an adult congenital heart disease tsunami hitting the adult health-care system – is not unique to Canada and is a global challenge," Dr. Oechslin says.

"It is our responsibility to bridge increasing patient demands and available resources so that we can continue to provide high-quality care to these patients."