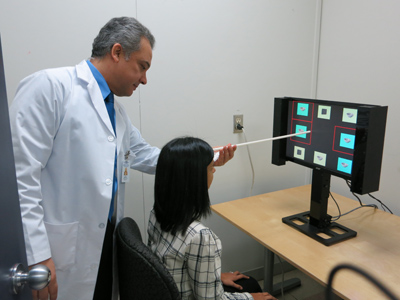

Dr. Ahmed Ebraheem, Canada’s first concussion research fellow, uses a visual scanner to test a patient’s cognitive reflexes. His research will evaluate whether certain technologies can detect the effect of concussions on the brain.

(Photo: UHN)

Nineteen-year-old Allison Haggart, whose snowboard career was ended by concussions,surpassed her goal of raising $100,000 for the Allison Project, which launched in January, 2013.

Nearly $130,000 will go towards funding a two-year fellowship devoted to answering in-depth questions about concussions – the first of its kind in Canada.

Dr. Ahmed Ebraheem, a neurosurgeon trained at Zagazig University in Egypt, was chosen for the position and has joined the Canadian Sports Concussion Project (CSCP).

The CSCP is a research team led by Dr. Charles Tator, a neurosurgeon at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre of Toronto Western Hospital.

Ebraheem's research will be supervised by neurologist Dr. Carmela Tartaglia, another CSCP researcher.

The CSCP is Canada's first project to address unknowns such as whether those who have had a concussion or multiple concussions are at greater risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease. Little is known about the long-term effects of concussions and specific treatments.

"I was ecstatic that we not only hit but surpassed the $100,000 goal," said Haggart. "It was a big number, and I admit I did feel some pressure to succeed. I credit our success to our ability to get organized, reach out, and to be blessed with very generous donors."

"Concussions are so prevalent and affect many people. I look forward to seeing how the Allison Project's contribution to this research will further our understanding of this brain injury," she continued.

Improving detection, assessment

Ebraheem is currently setting up the Toronto Western Hospital's Concussion Research Clinic which officially opens in February. As a neurosurgeon, he is familiar with concussions and the frustration of not being able to do more to help these patients. He hopes his research will change that.

"Concussion is still a very new area of research in neuroscience," he said. "It is very exciting to hold the first fellowship of this kind, and we are eager to not only better understand this injury but also hopefully find ways to treat it."

Through two studies conducted with his CSCP colleagues, Ebraheem will assess different technologies, such as a visual scanner and a tracking device as complements to clinical evaluation, for their ability to detect the effects of concussion on the brain.

He will evaluate patients who have suffered from the concussion spectrum of disorders including concussion, post-concussion syndrome and brain degeneration such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

It is hoped this research can establish a concussion index to better detect and assess the severity of the concussion spectrum of disorders, and determine the best course of treatment or rehabilitation.

"There is a very wide range of symptoms associated with concussion and its consequences, ranging from headaches and dizziness to emotional disturbances and problems with attention and working memory, and experts don't know the reason for this," Ebraheem said, adding, "Figuring out the mechanisms underlying concussion is very challenging, but once we get a better understanding of how it is happening, this may provide an avenue for treatment."

Devastating crash

In 2012, the promising career of Haggart, a former provincially-ranked snowboarder, boardercrosser and coach, came to an abrupt halt when she crashed on a ski hill north of Toronto. She was wearing a helmet and remained conscious.

Over the next few days, Haggart suffered from pounding headaches, dizziness, vomiting and disorientation. No one could explain to her what was happening inside her head to cause these symptoms, or offer her any treatments, other than time.

Doctors did, however, tell Haggart that because the risk of head injury was so high in snowboarding, she should never snowboard again. And because the risks outweighed the rewards for Haggart – she decided that it wasn't worth it to continue. As a result, she became an advocate for better understanding of her injury not only for herself but for all those suffering from the after effects of concussions.

Ebraheem admires Haggart's determination in trying to help researchers find answers to this complex injury.

"Allison could have had her concussion and done nothing. But instead she thought about participating and took a positive path to further this area of research," he said. "She didn't want to accept that there was nothing that could be done for her or other patients with the same condition, and it is this kind of spirit that leads to progress that will hopefully enhance concussion research."

RELATED