Jorge Pacheco

At age five, Sandra was still learning how to swim. Sandra's family, including her ten-year-old cousin Jorge, were spending a summer day at Bronte Creek. When lunchtime arrived, Jorge noticed that his little cousin was missing.

"She was wearing an orange bathing suit with white and yellow stripes," remembers Jorge. "So that's what I was looking for. She was drowning when I spotted her, and I pulled her out of the water. She called me her 'guardian angel.' It's something she'll never let me forget. Who knew I'd be able to live up to that title again, 40 years later."

On Mother's Day 2017, Sandra was diagnosed with stage-four colon cancer. The cancer reacted well to chemotherapy and stabilized, but it had already spread to the liver, causing the organ to shut down. Sandra opted to participate in Dr. Gonzalo Sapisochin's clinical trial at Toronto General, which uses living donor liver transplantation to treat colorectal cancer that has spread to the liver.

Sandra put out a heartfelt message on Facebook in June 2018. "My family and I read it and we were blown away that living liver donation was even possible. I realized that I had the same blood type as Sandra. We talked it over as a family, my wife, my son and my daughter – and we all agreed that me getting tested was the right thing to do. We wanted to help her, we had to help her."

Other members of Sandra's family as well as friends also came forward to be her donor. Due to volume, scheduling and availability, each transplant candidate only has one donor in testing at a time. Jorge completed the health history form and waited to hear back from the living donor liver team.

"I had been diagnosed early on with some minor sleep apnea. When they saw that on the form they said, 'that's going to disqualify you, you need to be in peak physical condition to do this.' At that point I realized they were just trying to look out for me as well. I was about 215 pounds at the time and needed to get down to 180 pounds."

Motivated by the prospect of saving his cousin's life again, Jorge began to exercise religiously. He modified his diet, cutting out sugar and saturated fats.

"When it was my time to start the testing, they realized that every time I came in, I was making progress with my weight and health. I felt fantastic. Mind you, I've gained everything back," he laughs. "My body needs that weight, I'm a construction worker. I need to be fit but I also need that weight on me for my work."

"I remember them asking me if I ever smoked. I smoked in my 20s – it was the 'in' thing to do – but then you find out it gets old fast. During testing, they told me that I had completely reversed any damaged that was done by smoking. My lungs are healed. It was a big surprise. Looking back at it now, my determination to help Sandra made me a healthier person. This whole process probably saved my life too."

Throughout the testing, Jorge and Sandra talked regularly. Jorge's optimism grew with each test. "After a round of testing, I remember calling Sandra and saying, 'Sandra, I know I'm going to be the guy that's going to help you.' She was a little skeptical because sometimes I'm too confident, but I think a positive attitude makes a huge difference."

Jorge was confirmed as a match and his surgery was without complications. Sandra's surgery was more complex and the strong dose of immunosuppressants required to prevent her body from rejecting the new organ took their toll.

"I recuperated quicker than Sandra. I was in hospital for just under a week. She stayed longer so they could keep an eye on her and make sure everything was working. When she was able to get up and walk, we went on little walks around the unit together. Her husband actually took a video of her beating me in a race."

Two days before Jorge was discharged, some family came to visit. "Our whole family – aunts, uncles, cousins, children, everyone – came to see me and Sandra. That's when it really hit me: Sandra was on the brink of death and we were given this opportunity to save her. It's life-changing."

Once he returned home, Jorge was anxious to get back to work. "There are some things in place like PRELOD but they have a cap – it's around $3,000 for 12 to 14 weeks – and because I was self-electing to do the surgery, I wasn't covered because I didn't get hurt at work. Financially, it was a little scary."

"My employer was super supportive. He donated to the Go Fund Me page that Sandra set up to help cover my expenses, but other than that, there wasn't much he could do."

Financial security during the donation process is the primary concern for most living organ donors. As of 2020, there is no national program in place to support living organ donors in the time they take off work to save a life. Financial compensations for living organ donors vary from province to province but qualifications are not always inclusive, and the maximum amount offered can only supplement household income, as opposed to support it.

Despite the financial stress of recovery, Jorge has no regrets about his decision, and continues to marvel at living organ donation.

"What's really cool about being a living donor is that potentially everyone has this power. You are in complete control of making a decision that is going to save a life. You have that within you. And you're not only saving that one person, you're going to help someone that's on the waitlist, and then all their family and friends who love them – you've got the power to help all of them."

Melissa Sidhu

In 1976, Donald Sidhu was born in Miami, Florida with biliary atresia. Due to blockages in the bile ducts inside and outside of the liver, infants born with biliary atresia experience loss of liver function, cirrhosis and eventually, liver failure.

Twenty-five years earlier, Dr. Morio Kasai developed the Kasai Procedure (or hepatoportoenterostomy). This groundbreaking surgery bypasses the bile ducts, allowing bile to drain into the intestines, slowing damage to the liver. Shortly after his birth, Donald became the first child in North America to receive this groundbreaking procedure from a team of surgeons led by Dr. William Brown at Variety Children's Hospital in Miami, Florida.

For Donald, the Kasai Procedure kept end-stage liver failure at bay until his mid-thirties. In that time, thanks to the pioneering efforts of individuals such as Dr. Thomas Starzl and Dr. Gary Levy, liver transplantation – including living liver transplantation – had become routine life-saving procedures offered to patients in end-stage liver failure.

In 2011, Melissa Sidhu, Donald's sister, was in work-up to donate a part of her liver to her brother. "They looked at my chart and they said, 'is this your brother's first liver transplant?' I said, 'yes.' And they just looked at each other. They couldn't believe it was possible that he was born with biliary atresia and at 35, he hadn't had a transplant."

After Melissa explained about the Kasai Procedure, "their jaws just dropped. They told me that my brother is the reason they still do that procedure today at Sick Kids Hospital because it works."

Melissa, who worked on UHN's Research Ethics Board at the time, hadn't told her brother – or any of her family – that she was in the process of getting tested.

"As soon as he was listed in January 2011, I started testing. Since I was working in ethics at the time, I knew that if there was any sign that I was being coerced by family, or being paid, I knew my application would be null and void."

"When he found out that an anonymous donor had come forward, Donald was so surprised. That's when I told him it was me. He was shocked. He didn't want me to do it, he was scared for me. It took some convincing."

Both Melissa and Donald are blood type O – the universal blood donor group that can only receive type O blood. Typically, those with O blood type have a longer wait on the deceased donor wait list, and living liver donation can provide faster access to transplantation.

"We didn't know when his health would take a turn for the worst – what if an organ didn't come in time? I told him, 'I need you to be realistic. What is the plan here? Because hoping for the best is not enough.'"

"Dr. Les Lilly also made a good point. He told Donald that by me donating, I wasn't just saving his life, I was also helping someone on the waitlist get an organ faster. I'd never thought of it like that, and Donald hadn't either."

With Donald convinced and Melissa's testing completed, the surgery date was set. In a mad rush to complete her projects and get her affairs in order, Melissa didn't have time to be nervous for her first major surgery.

"The weekend before, I had to meet with my family members to sign all the legal documents if, you know, I became incapacitated – it was for power of attorney and all that. I'll never forget it, we did the whole thing over dim sum. It was like 'you get my car, you get my house, can you pass the chicken feet?'"

"I finished my last work document at around 6:30 pm the night before surgery. I went to the St. Michael's cathedral, lit a candle for my brother, and said my prayers. Then I went home, ate dinner and packed."

Having watched the liver transplant program grow over the years, and knowing that its founder, Dr. Gary Levy had consulted with one of Melissa's mentors, Dr. Ronald Heslegrave for the medical ethics and consent process of living liver donation, Melissa felt she was in safe hands even though her family was nervous.

"My poor mother, she was with me while they were prepping me and she was so nervous. She was a medical surgical nurse and she just knew way too much about what could go wrong. I was in the gown, waiting to be taken in, and my mom is forcing me to do the rosary, trying to get me to take the world's tiniest prayer book into surgery with me, when my anesthesiologist Dr. Duminda Wijeysundera arrived. My jaw just dropped when I saw him – he was a member of my multidisciplinary research ethics board."

"When my mother saw the look of shock on my face, she just started laughing. Everyone started laughing and it just broke the ice. It was good. In that moment I was like, 'okay, this is a sign I'm not going to die, God is laughing with me right now, he's telling me everything is going to be fine.'"

Her colleague and anesthesiologist was the first person Melissa saw when she woke up in the recovery room, where she heard her brother's voice. Even though all donors who progress to surgery are perfectly healthy and ideal matches for their recipients, there's a three per cent chance that donors may not be anatomically viable candidates for donation; surgeons will only know for sure once they've started surgery.

"It's funny how your subconscious works. I guess I was worried about being part of the three per cent when I woke up. I swear I heard my brother's voice and I started panicking, because that would mean his surgery wouldn't have started. I was calling his name and one of the nurses came over and said, 'no, no, your brother is in surgery right now.' It was such a relief."

Post-surgery, in the step-down unit, Melissa and Donald were inundated with visitors.

"We have a huge family. I was worried the nurses were getting kind of annoyed because we had so many people there. My mom and my aunties brought so much food – they had a Filipino party in Donald's room. And my work was literally across the street so a lot of coworkers came to visit. It definitely wasn't lonely!"

Donald's recovery was without complications, and he was discharged within a week. But Melissa's white blood cell count had spike, though she had neither a fever nor an infection.

"And then it just got better. It was so strange. The specialist that came to see me every day was completely stumped, and it just went away," she shrugs. "Sometimes the human body is unpredictable."

Two and a half weeks after surgery, Donald and Melissa's family celebrated her birthday. Nearly 10 years post-surgery, Melissa is still happy to share her story.

"It was quite an experience, it really was, and I was really fortunate. Number one, I live in the same city as the living liver donor program, and number two, I was literally working across the street from the hospital. I can't imagine what it's like for people coming from outside the city, from out of province. It's a real privilege to live in Toronto, and be so close to this type of world-class, specialized medicine."

Though Melissa no longer works at UHN, she's not far from Toronto General. You can find her just up the street, at Women's College Hospital. As the newest member of the Centre's Volunteer Advisory Council, Melissa is not done with living liver donation.

"I just want people to know that it's really not as scary or as difficult as you might think. People treated me like I was a hero but honestly, I just lay there," she laughs. "And if I had to do it all over again, I would do it in a heartbeat. No questions asked. No reservations. Without a doubt, I would do it again. The team at Toronto General is amazing, they were born to be part of that team, to work in transplant – and it shows."

Nadia Larouche

In late spring 2013, Diane Lebrun's liver was starting to shut down. By June, she was in end-stage liver failure. Her doctors in Ottawa told her she would need a liver transplant.

"When I heard the words, 'liver transplant' I knew what would happen next," remembers Nadia Larouche, Diane's daughter. "I'm a person that doesn't like to sit on the sidelines. I need a plan of action. I started looking into being her living donor almost immediately."

Like most parents in her situation, Diane was resistant. Nadia reminded her what the doctors had said: that her liver failure, brought on by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), was progressing in a way that was unlikely to raise her MELD score. With a low MELD score, the chances of getting a deceased donor transplant are low.

Diane went to Toronto for assessment, and as soon as she was placed on the Toronto General transplant list, Nadia began her live donor assessment. From her initial research, she already knew that she needed to lose weight. There was also some concern about her family history of fatty liver.

"It was a lot of pressure on me. I had to diet for 8 months. It was difficult, but it gave me something to focus on. It's so disempowering to watch someone you love get sick. There are some truly horrible diseases out there where you can't do anything – at least with this I could do something."

Nadia was confirmed as a match for Diane and their surgeries were scheduled for early May, days before Mother's Day. When they removed Diane's liver, they saw she had started developing liver cancer. The transplant had come just in time.

"The first time I saw her, she was intubated – she had some complications during surgery – but even with her intubated and unable to talk, I was so struck by the colour of her face. I couldn't believe that in such a short period of time the life was back in her eyes."

For the first three months of recovery, Diane and Nadia were riding on a high. "She was a completely different woman. She was so lively and so appreciative. It was an amazing summer – for both of us. Living donation just changes your relationship to somebody in ways that words can't describe."

Near the end of the summer, the side effects of her anti-rejection medication started to wear on Diane in ways the family hadn't expected. "We took a downhill turn and it was rough. She had come such a long way and had been feeling great. She was on top of the world, only to go right back down. Her kidneys weren't functioning properly, she had gout – her side effects were horrible."

"I'm someone who likes to prepare myself a lot. I can handle anything if I'm prepared. I had no idea that the side effects could hit that hard. Seeing her in and out of hospital again was so frustrating. We all thought we were done with that. That's when she hit her lowest. They told us the first year is the hardest because the chance for rejection is high so the meds are at their strongest. The one-year mark became our goal. Low and behold, when we got there, things got better."

With a few years between Nadia and her living donation experience, she's been able to process the emotional impact of her mother's illness. "It was such a rollercoaster. I rode such a high in the summer and then came back down and then reality set in. You can't move backwards, you can't be who you were before, but you also can't stay in that heightened state forever."

"For a year of our lives, my mother's sickness defined us. Her disease was just non-stop. There was nothing else. It was her appointments, my appointments, extreme dieting and lifestyle changes, for a whole year. You lose yourself. I had a different identity during that time, and now it's over and who am I? My mom felt the same way. Who is she when she's not sick? We had to re-find ourselves, and that was a struggle, but we made it."

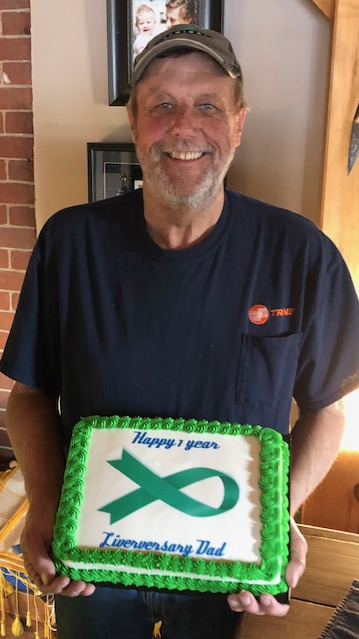

"We celebrate our liver-versary a little bit each year. It's really close to Mother's Day so that makes it extra special. I'm so grateful, we both are. We're grateful for every birthday, every Mother's Day, every Christmas – I don't take those things for granted. Living donation gave my mom a second chance at life. The time we're able to spend together is a gift."

Alana Long

Donation has always been a part of Alana Long's life. Her father was a regular blood donor when she was growing up, and as an adult, she has been donating blood for nearly 20 years. She is also a registered bone marrow donor. With such generous habits, it's no surprise that when Alana found out an acquaintance needed a liver transplant, she jumped at the opportunity to help.

"I was catching up with a friend over dinner," remembers Alana. "It's a bit convoluted but my best friend's dad is a gym teacher at my old high school. He found out that the wife of one of the other gym teachers, Karen, needed a liver transplant. I went to high school with her sons but didn't know them well."

Alana told her friend to pass along that she was willing donate. A couple months later, Alana saw their plea on Facebook for a donor, along with the link to the UHN Health History Form.

"I filled out the paper work and didn't tell them. I was waiting to know for sure before I told them anything, I didn't want to get their hopes up and have it not work out. As it was, I didn't have the most straight-forward process."

To ensure donor safety, Toronto General has strict criteria for living donors. In addition to the standard assessment tests, more tests may be required to ensure that the donor is in optimal health. For Alana, her doctors worried that she had fatty liver – which would put her at risk for donation. After her liver biopsy came back normal, Alana was cleared to be Karen's donor.

"When I told them, her and her husband were both speechless. They couldn't believe it. Karen wanted to make sure that I knew all the info, she was asking me all these questions, but I had just gone through the assessment so I knew more about the process than she did. They were speechless, and very grateful."

After sharing the news with Karen and her husband, Alana told her parents about her choice to become a living liver donor. "They were both super nervous. My mom especially, she was a wreck. The day before surgery my dad had his first opportunity to talk to some of the team and he asked a lot of questions. But they were supportive. I think they know better than to try and stop me from doing something I want to do. They embraced it."

Her hepatectomy was Alana's first major surgery. While she wasn't nervous, she was comforted to have parents in the hospital. "It was wonderful to have my mom come right into the PACU [post-anesthesia care unit]. I'm a pharmacy technician and I know they don't do that at my hospital. It was really nice to see my mom walking towards me right when I woke up."

Alana's surgery took longer than the standard eight hours. "I needed a few transfusions because they nicked a vein. My parents didn't know until after, thankfully. But they knew it was taking longer than normal. Dr. Grant said it didn't do any permanent damage to me, that it didn't take anything off my life, but it probably took some years off his," she laughs.

On the first day of her recovery, Alana's blood pressure dropped. "I still had internal bleeding, but they removed a clot and then I was fine. I was discharged after six days. They had stressed the importance of walking during recovery and my dad took that really seriously. He made a walking schedule for me."

Alana was well on her way to recovery, but Karen's outcome was still uncertain. Karen's surgery had been complicated. She was in the ICU when Alana was discharged. After three weeks in a coma, Karen slowly began to recover. A year later, Alana and Karen celebrated their one year liver-versary with their families. "It had been so nerve-wracking to leave the hospital, knowing that she was in the ICU, but I had faith she would pull through. And now, it's great to see that we're both doing so well."

With Karen recovered, Alana is finally able to reflect on the magnitude of her actions. "The feeling that you get when you realize you saved someone's life – it's something you can't get anywhere else. It's something you did. It's a very unique feeling. It's something I'm very proud of. I've been trying to put my story out there more and talk about living liver donation more openly. I want to keep helping. There's a man in my town who needs a liver, so I've been advocating for him and sharing his story to try and find a donor. We're working on it. I know we'll find someone soon."

Robyn McGrath

In 2016, Robyn McGrath was faced with an interesting question: what do you do when you're willing to give your parent a life-saving gift, and they don't want to take it?

Robyn's father, Robert, was in need of a liver transplant and Robyn's wish to be his living donor was met with resistance.

"My dad downright refused,” she remembers. "I had zero percent hesitation. I knew I was going to do it."

Robert worked as an industrial refrigeration mechanic until the day that he started showing symptoms of illness.

"It was one thing after another," Robyn explains. "He had celiac disease, varices, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, and kidney failure. He had two or three hernias as well."

Extensive testing revealed that Robert had cirrhosis of the liver. He would fight for a year before being airlifted from Ottawa to Toronto General, where he was placed on the transplant list.

Robyn started researching options for her father as soon as he was diagnosed. Living donation had been discussed just long enough for Robert to say that he wasn't interested.

"I was determined that it was going to happen," Robyn says "I was convinced that was what was going to save his life." Fueled by her resolve, she got to work.

"I sat down and printed 75 pages of statistics and information about living liver donation. I educated myself and I highlighted the important parts for him, like the fact that there are zero donor related deaths at Toronto General, that the liver grew back, things like that."

"At the end of dinner one night, I slapped the papers down in front of him and said 'here's some reading material. Before you make a decision, educate yourself, and make an educated decision.'"

Faced with Robyn's research, Robert conceded that without a living liver transplant, he was out of options.

Robyn started the assessment, pausing only when she stumbled over a fact she hadn't considered in her research.

"They did tell me that if my daughter ever needed a liver, I couldn't do this again. That made me pause for about two seconds. You can't bet on what the future holds. The chances are she'll probably never need a liver transplant. If we ever get to that bridge, we'll figure out a way to cross it."

Robyn was confirmed as a match and the surgery date was set for March.

During surgery, Robyn required a blood transfusion – she was bleeding more than normal – resulting in a slightly longer surgery. Other than that, things appeared normal.

Robyn's worst complication wouldn't be realized until seven days after surgery, when she experienced severe pain and couldn't eat. She had a twisted bowel and was rushed to emergency surgery.

After the second surgery, Robyn's recovery went smoothly. Her and her father's rooms were close by, which meant they were able to visit each other frequently.

"We were on such a big high. It was like magic, even with the complications. I felt like I'd saved his life; he felt like he had a new chance at life. And the fact that we're father and daughter, that made it really special for us."

Robyn is expecting her second child in September 2019. Since the transplant, her life continues on the same, but with a new perspective.

"To hear stories of people who haven't found their donor yet, it breaks my heart. I watched my dad really suffer. He struggled. He was dying. I want to promote organ donation in any way I can. It's more than just a check mark on your license. I want people to educate themselves. Even when things seem hopeless, there are options out there."

Patricia DeRoma

In the fall of 2017, Giuseppina DeRoma's health was declining. She had been diagnosed with non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver. She was 68.

"She was retaining fluid in her lungs," explains her daughter, Patricia. "She was in the hospital every other week to get her lungs drained. She was on oxygen at home, living in the living room, her quality of life was awful."

Giuseppina's liver was failing. She was placed on the deceased donor list but was told she would not survive the wait. Her best option was to find a living liver donor.

"I volunteered," says Patricia. "Out of all the children – me and my three sisters – I felt I was in the best situation to do it."

Despite her mother's resistance, Patricia and the living liver donor team started her assessment. Giuseppina's liver failure was working against them. On Patricia's first day of testing, her mother ended up in the ICU.

The following week, doctors informed Patricia that she had passed the first round of assessments but it was her choice if she wished to continue. They were uncertain that Giuseppina would be stable enough for surgery when the time came.

"I went back to my mom and told her what the doctors had said. Her MELD score was not high enough for her be pushed up to the top of the list, even though she was in the ICU. They were very frank with her. She realized that if she didn't accept me going through with it, she didn't have any other options."

With her mother's blessing, Patricia moved forward. She needed to lose weight to reach the minimum BMI requirement. Fortunately, she had already started when her mother was first diagnosed, just in case she would need to donate.

"When I started the assessment process, I was within 20 pounds of the requirement. I was so motivated. I didn't want to live with the regret of not having been able to try to donate. Whether I was a match or not, I knew that as long as I could be tested, that's all that mattered."

She was a match. Before the surgery, Patricia and her mother spoke privately.

"She told me she didn't want me to feel responsible for anything if it didn't work. She knew I was doing everything I could to help her."

The transplant was fraught with challenges and complications for Giuseppina; her recovery involved multiple subsequent surgeries. Patricia was in pain. She had never experienced a major surgery. Her biggest concern however, was her mother.

"As much as I had anticipated it might not go smoothly for my mother, it's one thing to anticipate and another thing to have it happen." The two-week post-surgery period was the most difficult. "I was so emotional and upset. But I was never alone. My mom and I had lots of visitors."

"The transplant team were super supportive. One of the days, I remember Zubaida came in with the surgeons on round. I was emotional and they told me that I had done everything I could for my mom. They were there for me, telling me I did what I had to do, and now they were doing what they needed to do."

While Patricia remembers the physical recovery as challenging, it was the emotional recovery that was the most difficult.

"I never spoke to anybody about it, but I'm sure I was struggling with depression after surgery. I don't know how you can't in that scenario. As much as I wasn't accountable for her outcome, I put a lot of pressure on myself. When I left the hospital, my mom was really ill and we didn't know if she would make it. I didn't know when I could come back to see her because we live far away. That first week at home was probably the hardest."

In the post-surgery period, it's crucial that living donors walk a little each day to prevent blood clots. But a little is a lot when you're struggling. Thankfully, Patricia had her 10- and 12-year-old nephews to get her up and moving. Their presence was a welcome distraction.

Eventually, when Giuseppina's health became more stable, Patricia started to feel better, physically and emotionally. After one month, she felt a real change; her energy started to increase.

Now, both Patricia and her mother are back to their normal lives. Patricia can't help but marvel at the change she sees in her mother.

"It's night and day. She was so sick and frail, she was doing nothing, she was housebound. Now she's out, she's social, she's put on weight, she looks healthier. Her quality of life has changed. It feels like it was a bad dream when she was sick. If I didn't have a scar, it would almost feel like it had never happened."

Playing an active role in her mother's transplant journey has also changed Patricia's perspective.

"I was very career focused, I still am, but going through this changed my perspective and reminded me how important it is to have balance. Living donation just changes how you think of things, how you approach things, and what matters to you. To me, it was a life-changing experience. Even though we went through so many highs, so many lows, I would do it again in a heartbeat."

Perhaps most significantly, Patricia's gift has brought her and Giuseppina closer.

"We have this bond that's hard to explain. She gave me life, and I gave her a second chance at life."

Sonia (Donor) and Jaime (Recipient) Munoz

Illness and recovery require perseverance. After being diagnosed with NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) in 2017, Jaime Munoz would spend a total of four months in and out of hospital. In that time his youngest child and only daughter, Sonia, would become his living liver donor and save his life.

In August 2017, Jaime made an appointment with his doctor. He was feeling tired. They discovered his hemoglobin was dropping rapidly. Shortly after his initial visit, he started retaining fluid. An ultrasound revealed he had cirrhosis of the liver.

"I was an alcoholic five years previous to being diagnosed. When they first told me I had cirrhosis, I thought it was because of that. When I was in the hospital I learned that it was NASH and that it had nothing to do with alcohol. It was a shock. I didn't know there were so many types of cirrhosis."

By September, Jaime's liver was failing. His thoughts were becoming cloudy as the unprocessed toxins wandered his body. His water retention was so severe it required draining. A complication during a draining procedure sent Jaime to the ICU where he would remain, unconscious, for three days.

"It was such a shock because he was perfectly fine, he was just tired," recalls Sonia. "And then he started to retain water and everything else just happened. He was told in late September that he had two or three months to live if he didn't get a transplant."

The doctors told Jaime that his best chance was a living liver donor. Sonia and her three older brothers went to get tested immediately.

"From that day forward I was living in the hospital," Jaime remembers. "I was put on a lot of drugs and it was like déjà vu, because when I was drinking, it had the same effect on my brain. My brain started working like an alcoholic brain again, doing the same type of stupid things that I would do when I was under the influence."

Seeing Jaime appear as if he was drinking again was just one more challenge his family faced.

"It was hard seeing my dad, basically on his deathbed, but also it was hard to feel for him because he was, I hate to say – "

Jaime is quick to interrupt her: "no, it's true!"

"He was a jerk," Sonia admits. "He was rude, he was mean. We knew he wasn't himself but it still hurt to hear things that he would say."

In late November, it became clear that Sonia was the best candidate, a fact that Jaime was only vaguely aware of given his physical state, and how his family anticipated he would receive the information. "I have three boys and one girl, the youngest. She's my baby."

The surgery was set for December 21. The family told Jaime the night before. He was so exhausted and foggy, he claimed he didn't want to do it, but his family persevered.

"On the morning of the twenty first we found out someone had passed away who was an organ donor," Sonia explains. There weren't enough operating rooms to accommodate Jaime and Sonia, as well as everyone who would receive life-saving transplants thanks to the deceased donor. "They were able to save so many lives, but we weren't able to do the surgery that day. We were crushed."

Uncertain of Jaime's future, the family got permission to bring him home for Christmas. On December 26, the hospital called Sonia with a new date. The surgery would take place in two days.

Although the surgery was successful, Sonia and Jaime's recoveries were challenging. As Jaime's skin transitioned back to its regular colour, Sonia struggled with the pain, unwilling to eat and walk for the first two days. After a week in the hospital, she was discharged. Jaime's recovery was plagued with complications, including nerve damage to his left leg and a bacteria in his stomach.

When he finally returned home, after four months in and out of hospital, Jaime had lost 100lbs, and was unrecognizable to his grandchildren, a fact you would have trouble believing if you saw him today.

Similarly, Sonia's appearance holds no evidence of her surgery. Her donation to her father continues to be a source of inspiration for her.

"I feel better than ever. To me it's something that hasn't held me back. I go to the gym regularly, I have a physically demanding job and if anything it's just pushed me to do more, to lift heavier, to run those extra miles."

Jaime is nothing short of grateful for his daughter's amazing gift, and for his family's perseverance throughout his illness.

"It's a miracle. You don't have to be a religious person to believe in miracles. I had great doctors, great surgeons, it changed my life forever. It changed the whole entire family, and all our friends. It's an amazing thing that could only have happened here, because we had the opportunity at Toronto General. The doctors, the nurses, even the janitors – without any of those people, we wouldn't be here. It takes a team."

Michelle Tone, Organ Donation Advocate

Illness is an unpredictable path. When Michelle Tone volunteered to be a living liver donor for a friend in end-stage liver failure, she never could have predicted where it would take her.

"Anne* was getting sicker and sicker. No one in her family was a match. So I threw my hat in. Without her knowing, I got tested. I don't know why but I felt intuitively that I would be a match."

After three months of rigorous testing at Toronto General, Michelle as confirmed as a match. Anne and her partner were thrilled.

"I was doing anything and everything to improve the health of my liver. Not that it wasn't healthy, but preoperatively they want it to be in the best possible shape. The transplant team really does prepare you extremely well. Whether you want to or not, you're going to come out of there knowing everything about living liver donation."

A week before the scheduled surgery, Michelle received a call about her most recent blood work. The surgical team wanted her to do another test immediately. The results came back two days before surgery.

"I was told I had a clotting issue: von Willabrand. I didn't know I had it. One of my parents is a carrier. They didn't know either."

Von Willabrand is a genetic disorder that is caused by a missing or defective blood clotting protein. If both of Michelle's parents were carriers of von Willabrand, Michelle would be a hemophiliac.

While Michelle's circumstances are rare, being ruled out as a donor late in the process is not unheard of. Even at the beginning of a liver transplant surgery, the living donor is still being examined to ensure their health and safety. Understandably, news like Michelle's is heartbreaking.

"I went back in and saw my transplant coordinator. She was devastated for me. At that point we had already told our friends that I was going to be the donor. My family knew, my girlfriend, Anne's family, we were all prepped for it. We had had a pre-donation party. We had done all of that."

Michelle wouldn't give up her donor candidacy without a fight. She spoke with the surgical team and her coordinator to ask what her options were if she wanted to go ahead with the surgery anyway.

"They heard me out, but ultimately they said no, we can't do this."

With a firm "no" still ringing in her ears, Michelle went home. Anne was in the hospital, the symptoms of her liver failure rapidly progressing.

"I felt like a failure. Not only could I not do it, but my friend was going to die."

But within 48 hours of Michelle's discussion with the living donor team, there was another call from the hospital, this time it was for Anne.

"It was five in the morning and she got a phone call saying there's a liver. It was from a deceased donor. They wouldn't know if it was going to work until the organ got to the hospital and they had a chance to look at it. There was another family there waiting. They needed a liver for their loved one too. It was either going to be them or us."

They waited, uncertainty looming over them. Anne qualified for the liver. The other potential recipient wasn't a match.

"We saw that family leave and it was just utter devastation. We were within a few feet of them. It was heartbreaking. It could've just as easily been us getting bad news. That turned me to faith quite quickly."

When Michelle came to visit the day after the transplant surgery, Anne was sitting up in bed, already well on her way to recovery. With Anne in stable health, it was time for Michelle to start her own recuperation.

"After I was rejected as a donor, I really had a hard time with it. I actually continued to see the psychiatric nurse who did my psychosocial evaluation. She told me that Toronto General had outlets and supports available to help people that were in my circumstance. I saw her for a few months and she really helped me move forward."

"As much as I struggled with the fact that I couldn't do it, I don't regret any of the time or money or emotion that I invested in it. It will always be a part of me."

Since Anne's transplant, Michelle has found other ways to help individuals coping with illness, and to advocate for organ donation.

"I realized there are so many ways to help. That's what made me found this Facebook group. There's 3,700 members now. It's worldwide but mostly US and Canada. Some of the stories on there are incredible. Everybody has a story, whether it's knowing somebody or being there yourself."

The community that Michelle has helped to create is rich with hope and determination. It's a collection of past and future donors, those undergoing assessment, those waiting for a transplant, family and friends.

"It's an upbeat page. There's not always a success story to be had but this group could be really morbid and it's not. That's what I like about it."

Since her experience with transplant in 2004, Michelle can see the progress that's been made in living donation, as well as the opportunities that still need to be seized.

"When I was going through the assessment, live donation was still so new. When I told my family, my friends, people thought I was crazy. And now people talk about it, there's education on it."

"But we still have a tremendously low amount of organ donation, which boggles my mind. It's not fair to say it's just a signature on your driver's license, it is more than that. But why take it with you when you could leave it here for someone? I would love to do something around that, and probably will. That'll be my next project."

*Name has been changed to protect the privacy of the individual.