For people with

white coat syndrome, simply the sight of doctors wearing white coats is enough to raise their blood pressure and anxiety level. While this may be a more extreme reaction, a certain level of trepidation is understandable for some procedures—particularly those that are considered to be 'invasive'.

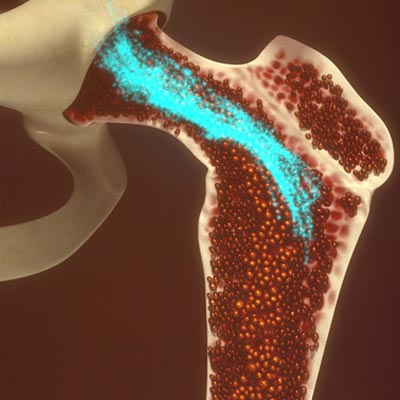

One such procedure, known as bone marrow aspiration, involves using a thick needle to penetrate bone and take a sample of the soft spongy tissue. This sampling of bone marrow is currently used to diagnose and monitor multiple myeloma, a type of cancer that affects white blood cells.

In the medical field, reducing harm, including the degree of invasiveness of a procedure, is an important part of treating and maximizing benefits for patients. Dr.

Trevor Pugh, Scientist at Princess Margaret Caner Centre, and Dr.

Suzanne Trudel, Affiliate Scientist at the Princess Margaret, helped do this for individuals with multiple myeloma by developing a less-invasive procedure: a blood-based test capable of monitoring the progression of the disease.

"Our new approach offers a much needed alternative to bone marrow aspiration, without compromising the ability to make medical decisions," explains Dr. Pugh. "It creates an opportunity to monitor multiple myeloma in those receiving therapy in real time, as well as to develop tests to detect the disease earlier."

The bone marrow (depicted in red-orange) contains hematopoietic stem cells that develop into all types of blood cells.

The approach they developed involves analyzing genetic material known as 'cell-free DNA' that is produced by tumour cells and can be found circulating in the bloodstream. When compared to the more invasive bone marrow aspiration approach, the new blood based test was able to accurately detect 96 per cent of the tumour-associated mutations—providing genomic information as good as that obtained through the traditional method.

"Importantly, our non-invasive test also makes it more likely that patients will participate in clinical trials of new treatments—accelerating the effort to develop new therapies for multiple myeloma and other blood cancers," Dr. Trudel says.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the Canada Foundation for Innovation; the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science; the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute; Myeloma Canada; the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation; and The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.