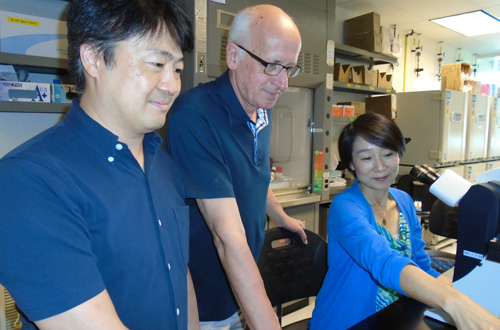

Dr. Shinichiro Ogawa, Keller lab, Dr. Gordon Keller, Director of the McEwen Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Dr. Mina Ogawa, Keller lab, look at the human bile duct cells they produced from human stem cells for the first time. Stem cell technology allows us to develop and test new treatments by studying diseases at a cellular level. (Photo: UHN)

A Toronto team of clinician-scientists and stem cell biologists has developed a powerful new method to generate 3D bile duct structures from human stem cells in order to study and develop new treatments for bile duct diseases.

Although bile duct disorders are well-recognized causes of liver disease, little is known about how these diseases develop. An ability to study these diseases in a Petri dish would allow a deeper understanding of the specific cell mechanisms that go awry, leading to a more targeted approach in developing and testing treatments for these diseases.

The findings from the study, entitled "Directed differentiation of cholangiocytes from human pluripotent stem cells," were recently published in the August 2015 issue of the high-impact journal

Nature Biotechnology.

Related to this story:

"Until now, we have not had a good scientific model to study the human liver's bile duct system," explains Dr. Anand Ghanekar, a Clinician-Scientist at Toronto General Research Institute and one of the senior authors. "We need to be able to study a patient's disease in a dish at the basic cellular and molecular level. Stem cell technology gives us a totally different way of evaluating and then treating these defective cells."

Dr. Ghanekar, who is also a transplant surgeon at University Health Network, and co-senior author Dr. Binita Kamath, a hepatologist from SickKids, treat patients with bile duct diseases. Bile ducts are tube-like structures found in the liver that carry bile—a substance that helps with detoxification and digestion – to the small intestine. Bile ducts are made of cells called cholangiocytes, which are the target of a number of chronic and progressive liver diseases, with few medical treatment options. These diseases are responsible for about 20 per cent of adult liver transplants and a majority of paediatric liver transplants.

Dr. Anand Ghanekar, a Clinician-Scientist at Toronto General Research Institute and one of the senior authors of the paper on developing bile duct cells from stem cells.(Photo: Anthony Tuccitto)

Wanting to find new ways to treat these diseases, Drs. Ghanekar and Kamath approached Dr. Gordon Keller, Director of The McEwen Centre for Regenerative Medicine, with the idea of generating bile duct cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Pluripotent stem cells have the capacity to give rise to most of the cell types in the human body. As the McEwen Centre is a world leader in producing different cell types from these stem cells, the team felt that the challenge of making bile duct cells had a good chance of succeeding.

Four years and several hundred experiments

The work at the McEwen Centre was led by Dr. Shinichiro Ogawa, a member of the Keller lab who had previously developed a strategy for making another type of liver cell known as the hepatocyte from human stem cells. Hepatocytes make up about 70 per cent of the liver and are involved in detoxification and the formation of bile.

Working together with his wife Dr. Mina Ogawa, a co-first author on the publication, Dr. Ogawa used clues from our understanding of how the bile duct develops in the early embryo to develop a new method to produce 3D bile duct-like structures from the human pluripotent stem cells in the Petri dish.

While it took four years and several hundred experiments for the McEwen lab team to complete the study, the ability to produce human bile duct cells represents a major step forward as it opens new opportunities to study how cholangiocytes and bile ducts develop within the liver and how disease affects this process.

Dr. Ogawa also sees other exciting opportunities in these advances.

"With our ability to make two of the the major liver cell types, we are now in a position to put the pieces together and produce a piece of functional liver tissue in the Petri dish. The ultimate goal is to some day transplant this liver tissue into patients suffering from liver disease," Dr. Ogawa says.

'A massive step forward'

Once the methods to generate bile duct cells from normal pluripotent stem cells were established, the McEwen lab team then set out to determine whether the technique could be used to model a bile duct disease, specifically cystic fibrosis (CF).

Many patients with CF have defective bile duct function and liver disease due to the same genetic mutation that causes lung disease. Using pluripotent stem cells derived from actual CF patients, and working with Dr. Christine Bear's laboratory at SickKids, the team showed that although bile duct cells and structures could form in a Petri culture dish, they did not function properly. But the function of the CF bile duct cells could be corrected by treating them in the Petri dish with new CF drugs that are currently being tested on patients.

These findings highlight the potential power of this approach for identifying other new drugs to treat CF. They also provide a new platform for modelling other diseases of the bile duct.

"For the first time, we can study the structure and function of bile ducts derived from patients' own stem cells," says Dr. Kamath, who is also an Associate Scientist in Developmental & Stem Cell Biology at SickKids. "This is a massive step forward in personalized medicine as the bile ducts carry any genetic changes that are unique to the patient. This will allow us to better understand bile duct diseases and ultimately develop targeted therapies."

Dr. Ghanekar adds: "This work is an excellent example of how collaboration between basic scientists and clinician-scientists can help to target cutting-edge basic research in a way that is immediately relevant to patients. The power of stem cell technology is to be able to identify and correct the disease at a cellular level, and one day, develop personalized, customized treatments including tissue replacements."