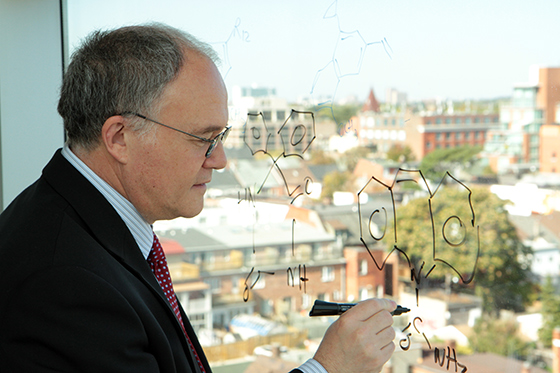

Dr. Donald Weaver, Director of Krembil Research Institute. (Photo: Research Communications)

Dr. Donald Weaver, Director of Krembil Research Institute. (Photo: Research Communications)

Dr. Don Weaver is a jack of many trades, and master of pretty much all of them. Physician, researcher, 'Origami Master' of drug design, multiple patent holder, "micropharma" founder, firebrand teacher, multiple award recipient, Tier 1 Neuroscience Canada Research Chair, even a prankster, upon occasion.

A rarity among researchers in the world, he is the only qualified person in Canada to be a practicing neurologist with a PhD in medicinal chemistry and drug design. From "away" or Halifax, Dr. Weaver was a professor in multiple departments in Dalhousie University and former Research Director for Medicine at Dalhousie Medical School and Capital Health; prior to Dalhousie, he was Chair of the Division of Neurology and Chief of Clinical Neurology at Queen's University.

And now, he is the new Director of the Krembil Research Institute.

You would think that a mantle of such achievements would be a staggering load indeed. But Don Weaver is quick, agile, always ready with a smile or quip, and uses any and all methods at hand to explain his passion for collaboration, teaching, creating small biotech companies, breaking down silo thinking, and above all, creating new drugs that don't just dampen symptoms, but actually cure illnesses.

"Going through the steps of taking a molecule and trying to move it ahead so that it really becomes a drug is fun, it's interesting, and ultimately, it's a lot more rewarding than simply putting a sentence at the front of your grant saying 'and these molecules may be relevant to Disease X'", he told Canadian Chemical News in a 2011 interview.

And Dr. Weaver has certainly delivered on his quest to create drugs from molecules. Working with a multidisciplinary team, using high-speed computers and quantum mechanics calculations, he designed one of the first "disease-modifying" drugs for Alzheimer's that reached Phase III human clinical trials worldwide. His lab also designed a drug for systemic amyloidosis, which has completed Phase III clinical trials. Amyloidosis is a disease in which an abnormal protein called amyloid accumulates in body tissues and organs, causing serious problems in the affected areas.

"Pretty good," he says, with a smile, for molecules designed in a Canadian university.

Currently, his lab is developing compounds for his latest biotech company, Treventis Inc., which can prevent the problem of "misfolding" in proteins gone wild. Left unchecked, these rogue proteins set off aberrant chain reactions leading to disease. His goal is to stop proteins which misbehave by "misfolding" themselves into the wrong shape, creating havoc in a human cell.

Hence, a possible new title for Dr. Weaver: 'Origami Master' of drug design. This is someone who understands the biological rhythm of a protein folding, twisting, turning and transforming itself into its final exquisite, correct 3-D form.

Dr. Weaver's pioneering platforms for drug discovery are so novel and complex that they score 17 on the level of difficulty and originality on a 10-point scale. And the scientific world has taken note, piling on laurels, distinctions, awards, honours and named lectureships: a highly competitive 2013 Wellcome Trust

Seeding Drug Discovery Award to continue developing a drug to cure Alzheimer's; the 2011 Jonas Salk Award for significant advancement in knowledge, prevention, treatment or cure of a disabling condition; the prestigious 2010 Killam Research Fellowship Award; the 2009 Prix Galien, known as the "Nobel of Canadian biopharmaceutical research"; Top 40 (leaders) under 40, the U.S. 2007 Centennial Award for being "one of the two researchers in the world with the highest likelihood of discovering a 'curative' drug for Alzheimer's" and so many others.

The unusual way in which Dr. Weaver approaches a biochemical challenge extends to his formidable ability to navigate uncharted medical terrain, the way in which he leads his teams in the face of high-risk failures, to how he draws on the collective strengths of typically siloed academic fields to achieve insights and breakthroughs. He is not afraid to use the "b" word,

breakthrough - said rarely and then only in hushed tones in academia - or "soaring" to describe high impact research which is "nurtured" in a "supportive environment of excellence". This, he says, is what will ultimately produce novel diagnostic and therapeutic products for chronic diseases of the nervous system, the eyes and the musculoskeletal system.

Achieving this goal, which he firmly believes is attainable, will propel Krembil to become one of the "top-5" medical research institutes in the world.

One of the many innovations that Dr. Weaver brings to Krembil is the concept of micropharmas as taking on the risks that were once the sole domain of Big Pharma.

Consider that from 1996 to 1999, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 157 new drugs. A decade later, from 2006 – 2009, that figure dropped to 74 approvals. None of these drugs actually cure a disease, or, it could be argued, even effectively treat many of the diseases that ravage human lives such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, epilepsy or deep depression.

So, where are the cures?

They're stuck in the grey zone between a lab bench and a prescription pad. The so-called valley of death.

Academia and granting agencies reward basic discoveries, but not necessarily the work that turns these breakthroughs – there's the b word again! – into actual drugs. That's where the micropharmas come in.

Drs. Weaver and Chris Barden coined the word "micropharma" in a 2009 paper published in

Drug Discovery Today called "The Rise of Micropharmas". Essentially, these are biotech companies that are small, efficient, flexible, product-focused and linked to academia, universities, hospitals or research institutes. They favour high-risk approaches, and are prepared to do the heavy lifting of first discovering a therapeutic agent and its mechanism of action, and then evaluating how the agent behaves over a period of time, and its toxicity.

With this information, micropharmas can entice Big Pharma into partnerships, to broaden Big Pharma's "shockingly depleted" drug discovery pipeline and the treatments which Big Pharma has "failed to deliver" for diseases which now threaten to overwhelm the developing nations, according to the blunt 2009 paper.

"Every drug is a molecule, but every molecule isn't a drug, so you want it to withstand the long arduous trip from gums to whatever the target is in the body. It has to…[ work], and it has to be safe," said Dr. Weaver in a 2011 interview with Tyler Irving from Canadian Chemical News.

Without that initial gruelling work, as well as patent protection, no Big Pharma is willing to risk its resources and money to run big human clinical trials and navigate regulatory agencies, which it does very well, he adds. Dr. Weaver has, so far, co-founded eight micropharmas.

When Irving Tyler asked Dr. Weaver how he faces such a high-risk, uncertain environment day after day without giving up, Dr. Weaver replied:

"You have to look at failure as steps in the ultimate road to success. If you're not failing, you're not working hard enough."